Ceramics

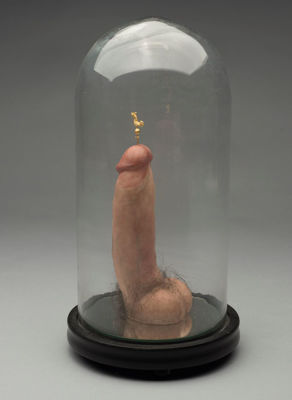

Title: The Stinkhorn, Glorification I

The glass bell symbolizes the seclusion of the core family, the church, the family, and the neighborhood. In fact, it is the protective cocoon in which people feel safe and protected. This protective cocoon may quickly become a means of hushing things up that feels like a prison. For seclusion often leads quickly to silence. In this form, the glass bell is both a fragile barrier and at the same time, an impregnable fortress. We look at it and yet cannot reach the situation. This is a feeling that exists in many people. You have to stand outside in order to see it, but it requires courage to smash the glass bell to pieces and break the silence. The generative power in nature: the body is finite, sexuality is timeless, and finiteness also contains infinity. The Stinkhorn In this image under the glass bell, Arnix has turned power into something fragile. For him, the stinkhorn (phallus impudicus = unashamed penis) forms the symbol of transience of power and potency. It can be compared to the present position of the church: an institute quickly losing power, stature and influence because it turns out to be an institute without mechanisms for renewal and rising up again. The influence of this mighty institute is crumbling continuously. The crown of thorns on the stinkhorn’s head is a reference to the crown of thorns (Christ thorn) from Jesus’ crucifixion. It creates a symbol for suffering and mockery. The symbolism of the dying of Jesus and cleansing of sins by the church is totally stripped of gloss. The staffs that were there to spread the word have fallen into sin, and have weighed their victims down with it. The fly, subtly present, stands for slander and corruption.

Title: The Talking Head-Hand-Heart

Stipl utilises his technical skill to create shocking, discomfortingly realistic figural sculpture that expresses the human form locked in thresholds of pain or primal emotion. Often the works develop as tableaus, the multiples of personality produced by Stipl each clashing and repeating themselves in sequence. ‘Strawberry Cream’ explores this to fruition with the grid-like locking in of a babies’ head — each individually rendered emotion quickly giving way to a larger wall of noise, and an audiences’ vague horror and even revulsion towards the wax-like primordial substances in which they are embedded.

Title: The Tower, Glorification I

The glass bell symbolizes the seclusion of the core family, the church, the family, and the neighborhood. In fact, it is the protective cocoon in which people feel safe and protected. This protective cocoon may quickly become a means of hushing things up that feels like a prison. For seclusion often leads quickly to silence. In this form, the glass bell is both a fragile barrier and at the same time, an impregnable fortress. We look at it and yet cannot reach the situation. This is a feeling that exists in many people. You have to stand outside in order to see it, but it requires courage to smash the glass bell to pieces and break the silence. The generative power in nature: the body is finite, sexuality is timeless, and finiteness also contains infinity. The Tower The very dominant phallus within that same enclosure of the glass bell requires no further explanation. It is an impregnable power phenomenon that enforces silence. It is the church tower, the exclamation mark of dominance; power and omnipotence crowned with the golden cock proudly standing on top. The cock, as a symbol of brave vigilance or compliance. The cock always looks ahead, never backwards.

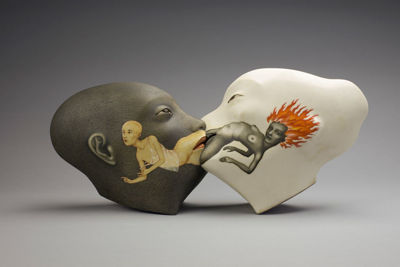

Title: To Kiss

Painting, sculpture and pottery annex under Isupov’s hand, the artist seeking to insert visual information at every level of an object’s surface and detail. “To Kiss”’s figurative balance — two heads caught in a moment of de-gendered intimacy — finds an elegant and dreamlike contrast in the qualities of surface and position. The painting tattooed across their cheeks suggests much deeper running (implicitly feminine) sexual fantasy or implication, Isupov’s careful detail finding a remarkable communion between 2d and 3d location.

Title: Top Dolly

Keelan’s sculpture confronts age and decay, focusing on a traditionally female perspective with her assumption of the doll — and the deeper psychological profile and momentary assumption (and subsequent loss) of youth embedded within it. ‘Top Dolly’ is a particularly gravity-defying piece, the doll seemingly having been spiked and sunken into a surface. The scuffed and scratched surface of the form alludes to wood, but is carefully realised and stained ceramic — the decaying texture simultaneously signalling a breaking down from user wear and significant passage of time. Semi-grotesque, the playful aspect is undercut with an unholy presence that can’t help but capitulate to notions of death.